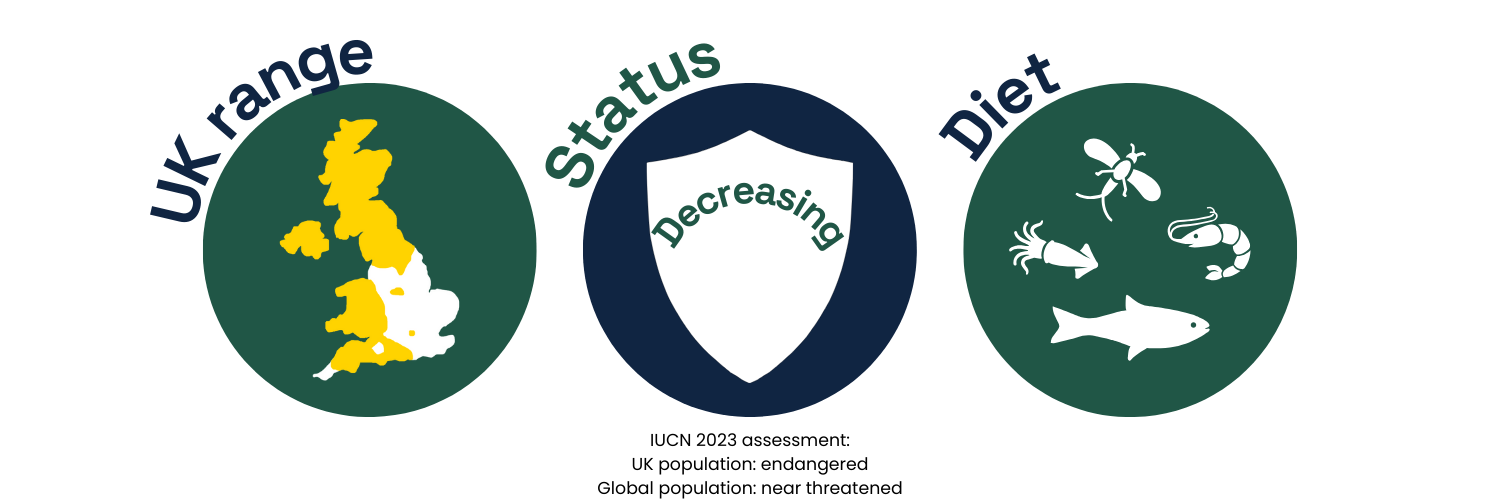

Over 10% of our freshwater and wetland species are threatened with extinction and at least two-thirds are in decline. If we don’t act now to save freshwater we risk losing these species altogether.

Donate to protect wild fishOver 10% of our freshwater and wetland species are threatened with extinction and at least two-thirds are in decline. If we don’t act now to save freshwater we risk losing these species altogether.

Donate to protect wild fishHere are some of the wild fish we work to protect. Click on a species to expand the box and find out more about them. Our work has a particular focus on Atlantic salmon as a keystone species and indicator of river health.

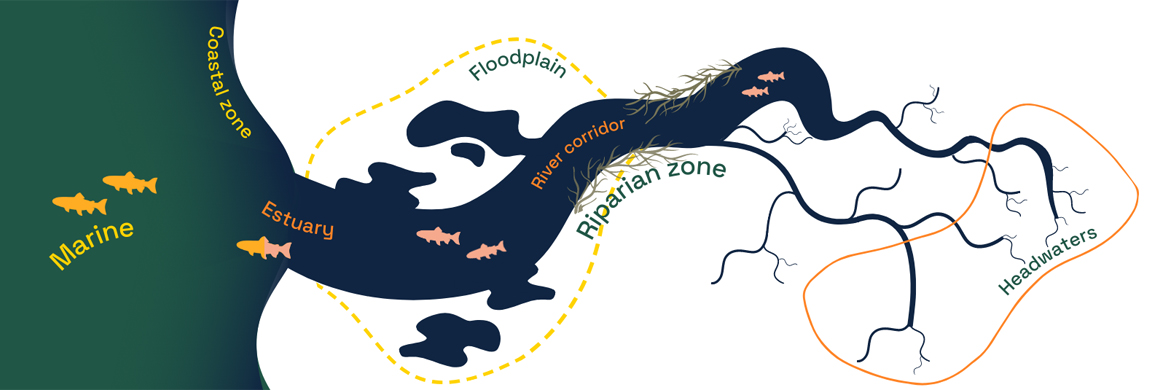

Water must be able to flow uninterrupted longitudinally (from its source to the sea) and laterally to connect with its floodplain. This is known as habitat connectivity which allows wildlife to move freely and supports biodiversity. Click on the wetland habitats below to find out more about the many different environments that make up a river system.

Headwaters are the permanently flowing streams that feed a river system. Typically, they extend up to 2.5 km from the source.

A large river system will have many streams that feed into it over its length. These are also known as tributaries.

70% of the river network in England is made up of small streams. They have diverse conditions depending on the geology, altitude, and land use in the surrounding landscape.

Headwaters are important to the whole river system as they allow species to be transported down river and establish populations in the lower reaches. This is a vital function when the lower reaches of a river lose species because of pollution.

Headwaters are particularly vulnerable to agriculture because they have a low volume of water. The low water volumes limit dilution, so pollutants or sediment that pass into the stream will be in higher concentrations.

Rivers are connected systems, so what happens in the headwaters can affect the whole river and its species.

A river corridor is the area of land that a river influences. This includes the river channel and any land to either side, such as wetlands and floodplains.

The riparian zone is the land beside the river that is affected by its presence. Riparian habitats include specialised plant and soil communities that can tolerate being partially or totally underwater.

Riparian forests and floodplains can reduce flooding, reduce transmission of sediment and pollution into rivers, sequester carbon and keep river water cool.

65% of floodplain zones are now occupied by intensive agriculture and 99% of rivers have had their riparian habitat altered by agricultural land use.

1. Changing land use

Riverbanks are modified and channels are straightened, sometimes reducing the length of a river by up to 50%.

2. Removal of important bankside habitat features

Submerged root systems, ponds, and rivulets are damaged when riverbanks are modified. Riverbank modification also changes flow regimes and destroys habitat for juvenile fish, macroinvertebrates, and birds.

3. Low water availability

Riparian vegetation is very vulnerable to low water availability. Loss of this habitat reduces the diversity of the invertebrate community, as well as the total species abundance.

The coastal zone is where the river meets the sea and where freshwater and saltwater mix. The intertidal zone is the area of land between the low tide and the high tide.

This is a particularly stressful place for migratory fish, such as salmon, who undergo smoltification – a complex series of physiological changes where juvenile salmonid fish adapt from living in fresh water to living in seawater.

Erosion, sea level rise, ocean acidification, and pollution are all at play. These habitats and the wildlife that they support are also vulnerable to disturbance by people.

1. Species diversity

The intertidal zone supports important biodiversity including seagrass meadows, saltmarshes, mudflats, and rocky beaches. The UK’s seagrass meadows capture carbon worth up £5.3m.

2. Defence against coastal erosion

Mudflats and saltmarshes are an important defence against coastal erosion and support unique communities of plants and animals. It is estimated that protection by coastal wetlands instead of sea walls saves up to £4,600 per metre of coastline.

3. Special habitat, nurseries and breeding ground for rare and migratory species

Species that live in this habitat need to be able to survive being submerged by the sea when the tide comes in and completely dry when the tide goes out. The specialist plants that live here are known as halophytes because of their ability to survive in salt water. Many of these are rare and endangered because they can only be found in these special habitats.

Coastal habitats in the UK provide globally important breeding grounds for many migratory birds.

The marine environment covers 71% of the earth’s surface. The seas and oceans that make up this environment contain many diverse habitats and lifeforms.

1. Chemical and plastic pollution

Freshwater sources run into the sea and many of the problems of chemical and plastic pollution in freshwater impact the marine environment too.

2. Climate change

Climate change is having a disproportionate effect on the oceans, warming them at an alarming rate. This temperature rise is causing ocean acidification.

These significant changes are affecting marine species. Many are changing where they live or experiencing population declines.

The marine environment also supports freshwater and terrestrial life.

1. Marine phytoplankton

These tiny photosynthesising plants and bacteria produce up to 50% of the world’s oxygen. This is despite having only 1% of the biomass of all the terrestrial plants on earth.

2. Feeding grounds

Marine environments are important feeding grounds for species like Atlantic salmon and sea trout. These salmonid species rely on marine food that is only available outside of the rivers they are born in to grow to a size that helps them breed successfully.

Over 85% of the world’s chalk streams are found in England and they support lots of important wildlife. They are often referred to as England’s rainforest.

England’s chalk streams support a genetically distinct population of Atlantic salmon which have adapted to the specific environmental conditions provided. Chalk stream water also supports many sensitive species of macroinvertebrates.

Chalk streams flow from underground chalk aquifers through landscapes dominated by chalk. This generates beautifully cool, clean, and clear water.

Winterbourne chalk streams are areas that only have flowing water for part of the year, known as ephemeral streams. These support both terrestrial and aquatic species over the course of the year.

1. Over-abstraction

Chalk streams provide over 70% of the drinking water in the Southeast of England and are vulnerable to excessive water extraction.

2. Pollution

Taking too much water out of chalk streams concentrates pollution within the river. Reducing the volume of water in these habitats can warm the stream to temperatures that are damaging for species present including salmonid eggs.

Support like yours allows our determined campaigning team to fight the destruction caused by open-net salmon farming, pollution and over-abstraction

Find out about all the ways in which you can help wild fish…