Why wild Salmon Face critical risk on the west coast of Scotland

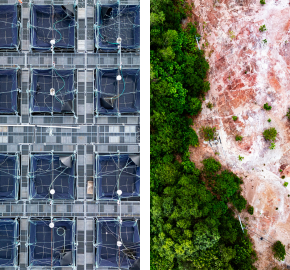

Our natural environment increasingly faces threats to biodiversity, ecosystem productivity and habitats. Wild fish are no exception but, on the west coast of Scotland, wild salmon face additional and critical risk from the impacts of open-net salmon farming.

Without stronger Government regulation, for which we have been campaigning vigorously, wild salmon will continue to be harmed by the fish farm-derived sea lice which are widespread in Scottish sea lochs, found in numbers far higher than any natural background. Add to that the impact of mass escapes and fish farm pollution and you have a serious problem.

Scottish Government intends, based on recommendations from the Salmon Interactions Working Group, to introduce a new system of monitoring for sea lice and responding to changes known as “adaptive management”. This system monitors sea lice populations on wild post-smolt sea trout (a proxy for wild salmon smolts) within a certain radius of open-net salmon farms and possible preventative action, to reduce on-farm sea lice numbers, only taken if monitoring of the wild fish demonstrates adverse impact at a population level.

WHAT IS THE PROBLEM WITH THE SCOTTISH GOVERNMENT’S PROPOSALS FOR ADAPTIVE MANAGEMENT?

Practically, the process of adaptive management means a lengthy delay between monitoring wild fish and any action on farm.

Sea lice can travel over 30k from a salmon farm. Decisions will need to be made on how many different locations need to be sampled for sea lice on wild fish, over what period of time, and how many fish need to be sampled? What if wild fish cannot be caught?

The proposed system can only work if a very significant number of monitoring sites are chosen, over a large area (up to 2800 sq.km.), a process that will take time to set up. The proposals raise serious questions if such a mammoth effort can really be resourced.

Inevitably, to produce reliable findings, it will take a considerable time for sufficient data to be collected – indeed, it is likely to require monitoring over several salmon farm production cycles. In fact, during a video conference in July 2020 a senior executive from the Crown Estate Scotland did not disagree that it would probably take intense monitoring of wild fish for at least three farm production cycles (up to six years) for any pattern of damage to wild fish to be discernible.

Time, we believe, that wild salmon don’t have.

Additional questions will then be raised about how the data is interpreted. Who decides what a suitable course of action on the fish farms to stop the damage is? And where you have many fish farms, often owned by different, competing companies, which farm needs to do what?

It seems likely that the opportunity for dispute and challenge (including legal action by salmon farmers), is enormous. We have seen how fish farmers are very happy to appeal against planning decision that go against them, they will no doubt do the same with adaptive management. This will cause even further delay before wild fish get the protection they need.

SO, WHAT IS NEEDED FOR EFFECTIVE REGULATION OF SALMON FARMING IN SCOTLAND?

Put simply, the key to effective regulation is a universal and robust farm sea lice upper limit.

Alongside, properly independent mandatory monitoring of fish farms and real – time reporting of data.

There should be a strict sea lice limit for adult, female salmon applied to all farms in Scotland. This should be set at 0.5 per farmed fish, dropping to 0.1 per farmed fish during the period of wild smolt migration.

Before adaptive management can be considered, we need action on the clear and easily enforced precautionary system of regulation, to control sea lice numbers, which was endorsed by the two Scottish Parliamentary Committees (which carried out the inquiry into salmon farming in 2018).

We need a system designed to prevent harm, rather than one that waits for harm to occur.

The current proposals, supported by both Fisheries Management Scotland and the Atlantic Salmon Trust, now under consideration by Scottish Government, conspicuously exclude any upper sea lice limit to be applied across all farms. There is no independent monitoring of on-farm sea lice being proposed – the fish farmers will continue to ‘mark their own homework’. Added to which there are no punitive sanctions for breaches. Fundamentally, the proposals do not pay any heed to the precautionary principle, contrary to the recommendations of the Parliamentary Committees in 2018.

Our focus remains strongly on achieving a tough, regulatory system that can be clearly and easily enforced. One that is transparent – with no cosy agreements made behind closed doors. That system must include an on-farm sea lice limit, independent monitoring of fish farms and mandatory reporting.

With the continuing expansion of the industry, effective and enforceable regulation of open-net salmon farming in Scotland is now needed more than ever.

Wild Atlantic salmon trying to reach spawning grounds. Image credit: George Clerk.