Salmon farms: in hot water

The recent heatwave has had devastating and wide-reaching impacts for habitats across the country, including in our coastal waters. We are all discovering how poorly equipped this country is to cope with rising temperatures, and salmon farms are no exception.

Scottish Atlantic salmon farms rely on cool water in sea lochs to operate, but as sea temperatures rise, following weeks of hot weather, this can lead to big problems on farms. An unfortunately predictable consequence of the heat is outbreaks of parasitic sea lice.

The sea lice life cycle

The life cycle of sea lice is highly temperature dependant. As the water gets warmer in the hot weather, they can complete their lifecycle quicker and quicker. One study found that an increase in water temperature from 9°C to 11°C doubled the infection pressure on Atlantic salmon farms from sea lice, while another found lice were most successful at infecting salmon between 12°C and 15°C.[1], [2] This was a result of not only their increased reproductive capacity but also increased vulnerability of the Atlantic salmon, which are not adapted for higher temperatures.

The lice have an easier time attaching to salmon in the warmer water. The average water temperature in Scotland in July ranges from 12°C to 16°C, and August has the warmest sea temperatures of the whole year.

The data speaks for itself

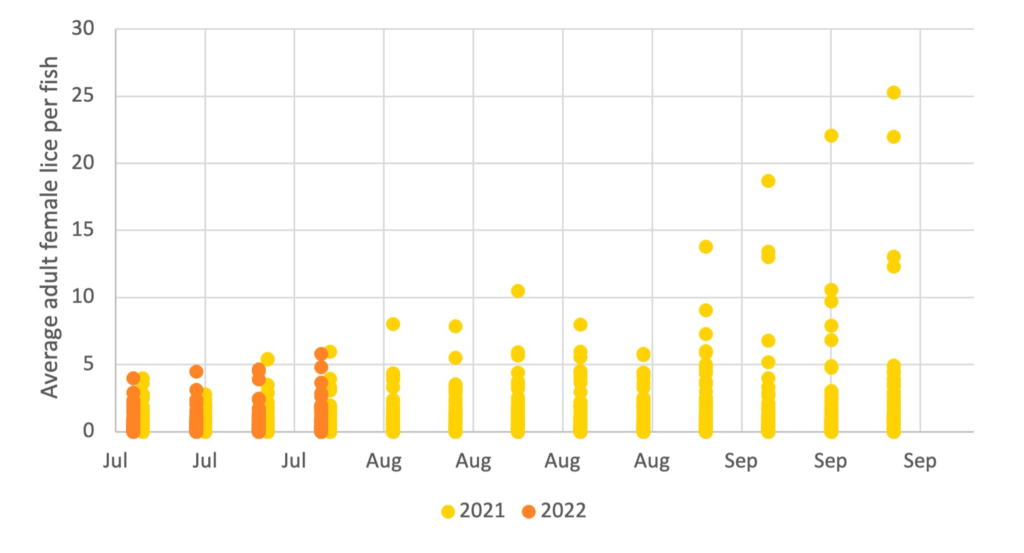

Last year August saw record high numbers of sea lice on salmon farms in Scotland. Guidance produced by the salmon farming industry body Salmon Scotland suggests that 1.0 lice per fish on average is the safe limit, but last year one farm exceeded 25 lice per fish! With the data for July now available (shown in figure 1) it seems likely history will be repeating itself.

Sea lice numbers have been steadily climbing across farms throughout July. Many farms already significantly exceed Salmon Scotland’s guidance and have reached the point of needing careful monitoring by the Scottish Government’s Fish Health Inspectorate.

The impact of increasing sea lice numbers on wild fish

This is not just a welfare concern for the salmon on farms suffering from these huge parasite infestations. Open-net salmon farming allows transmission of sea lice from farms into the wider environment. The juvenile stages of lice float in the water current to disperse, so they move freely out in the sea lochs where wild Atlantic salmon and sea trout live. The biomass of salmon in farms is one of the best predictors of the infection pressure from lice on wild salmonids.[3]

Outbreaks in farms are a serious concern for the health of wild salmonids.

It isn’t just warmer summers we need to worry about. Usually, the cold winter sea temperatures act as a break in the reproductive cycle of sea lice populations. Below about 5°C sea lice have very low rates of reproduction, and the sea lice numbers on salmon farms fall to lower levels. But as winters get warmer, there is no reprieve for salmon from these parasites and they can continue to proliferate throughout the winter.[4] This means wild salmonids will be at a greater risk to dangerous infestation pressure from farms for even longer periods of the year.

Current Scottish Government regulations do not protect our native Atlantic salmon and sea trout populations from sea lice originating on salmon farms. As the hot weather exacerbates on farm conditions it is distressing quite how inadequate these “protections” are proved time and time again at the expense of our wild fish.

List of references

- Dalvin, S., Are Hamre, L., Skern-Mauritzen, R., Vågseth, T., Stien, L., Oppedal, F., Bui, S., 2020. The effect of temperature on ability of Lepeophtheirus salmonis to infect and persist on Atlantic salmon. Journal of Fish Diseases 43, 1519–1529. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfd.13253

- Sandvik, A.D., Dalvin, S., Skern-Mauritzen, R., Skogen, M.D., 2021. The effect of a warmer climate on the salmon lice infection pressure from Norwegian aquaculture. ICES Journal of Marine Science 78, 1849–1859. https://doi.org/10.1093/icesjms/fsab069

- Penston, M.J., Davies, I.M., 2009. An assessment of salmon farms and wild salmonids as sources of Lepeophtheirus salmonis (Krøyer) copepodids in the water column in Loch Torridon, Scotland. J Fish Dis 32, 75–88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2761.2008.00986.x

- Ugelvik, M.S., Mæhle, S., Dalvin, S., 2022. Temperature affects settlement success of ectoparasitic salmon lice (Lepeophtheirus salmonis) and impacts the immune and stress response of Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar). Journal of Fish Diseases 45, 975–990. https://doi.org/10.1111/jfd.13619