Scotland’s Great Salmon Escape: A Continued Crisis

Mass escapes of Scottish farmed salmon into our rivers are a frequent occurrence, impacting the health of our wild populations. In this blog, we share new analysis that shows just how serious the problem has become, and explore what needs to be done about it.

When 75,000 farmed salmon swam free of Mowi’s Gorsten site in Loch Linnhe during Storm Amy, it was immediately framed as an “escape”. And yet, like all the previous times that farmed salmon have spilt out of these densely stocked cages, the “genetic pollution” of our rivers and sea lochs by these fish – selectively bred to grow fat fast for ignorant global markets – is rarely mentioned.

The word “escape” matters. It gives the illusion of choice, as if the fish plotted their departure. The vocabulary masks the company’s responsibility to prevent it from happening in the first place; a failure of engineering, not behaviour.

Since then, anglers on the River Lochy and elsewhere have been quietly doing the work that should not be left to them: intercepting farmed fish before they push further into already pressured wild salmon rivers. A focused effort on the Lochy alone has landed well over a hundred suspected escapees, with more still turning up, adding to Fishery Management Scotland’s growing database documenting regulatory failure.

One widely shared post shows a campaigner physically returning fish to the Gorsten pens, under the caption “lost property returned” – a protest that makes clear that public volunteers are trying to deal with a corporate failure.

SEE MORE HERE

Storm Amy wasn’t an especially unusual occurrence and Loch Linnhe is a relatively sheltered sea loch, particularly from north-westerlies, which predominated in Storm Amy. We get storms in Scotland. They are a fact of rural life. CalMac and the other ferry companies prepares for them. Fishermen prepare for them. Imagine those businesses didn’t acknowledge storms as predictable and accepted such routine damage and pollution as inevitable?

WATCH THE LONG LIVE LOCH LINNHE VIDEO

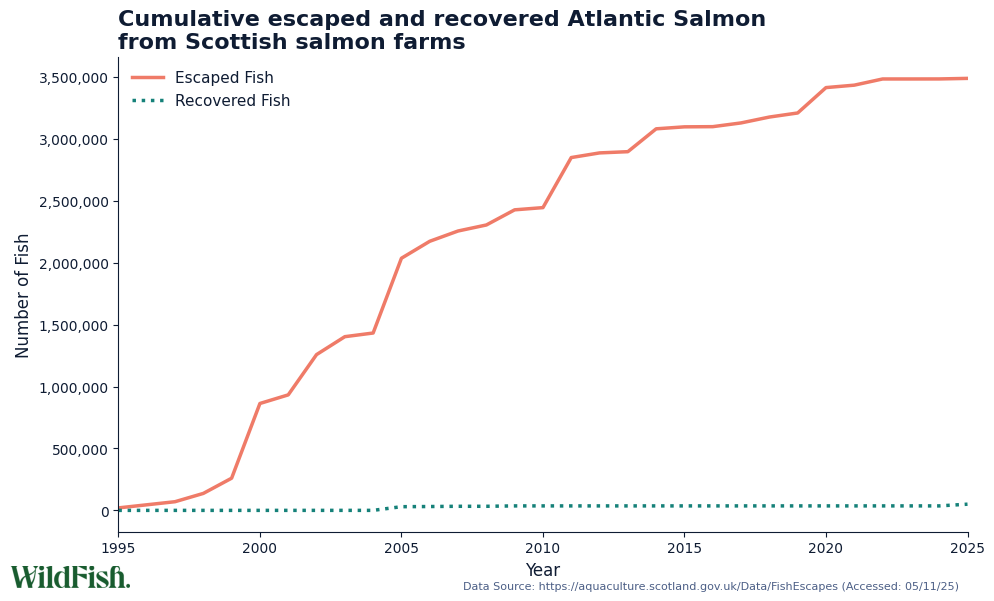

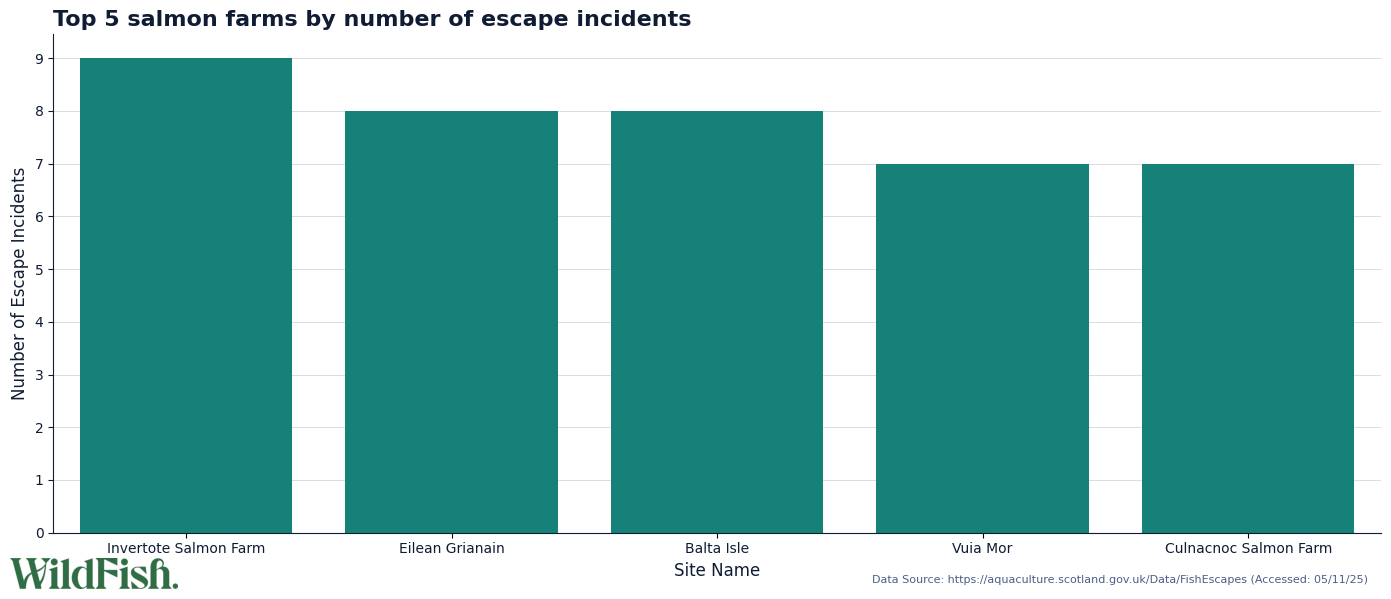

There have been hundreds of ‘escape’ incidents from Scottish salmon farms in the past 30 years. This isn’t an isolated story of bad luck in a big storm. It is part of a pattern, recorded in the Scottish Government’s own data.

The scale of the problem

WildFish analysis of the official farmed fish escape database indicates that since those records began three decades ago, reported salmon escapes from Scottish farms total in the region of 6,000 tonnes of fish. That equates to likely well over three million farmed salmon accidentally released into Scottish waters.

Let’s compare that to the current NatureScot estimates that roughly 400,000 wild Atlantic salmon now return to Scotland’s rivers each year, down from around a million in the 1970s. “Farmed salmon escapees – even on conservative assumptions – amount to 8 times today’s wild population. This is a disaster but the reality is almost certainly far worse.

The ecological consequences are not theoretical. Marine Scotland Science has found evidence of farm-bred genes in wild stocks at roughly a quarter of the sites it sampled across the country – a clear signal of genetic introgression, where escaped farm fish breed with wild ones and weaken their survival traits. Comparable Norwegian research shows those hybrid offspring are far less likely to survive to adulthood.

In short, every mass escape adds to a cumulative, long-term erosion of the genetic fitness of Scotland’s wild salmon. That should be framed plainly as a strategic risk to a species now listed as endangered — not as an accounting footnote.

Why the official figures understate reality

The 6,000-tonne figure should be treated as a minimum, for three reasons.

1. The reporting framework leaves space for uncertainty

Under the Aquatic Animal Health (Scotland) Regulations 2009, businesses must immediately notify Scottish Ministers of circumstances likely to have caused an escape or created a significant risk, and then provide a “final notification” of numbers within 28 days. That final figure is necessarily an internal estimate, produced weeks after the event, often based on back-calculating what might have been in a pen. By then, nets are repaired, fish have dispersed, evidence has gone. There is no independent census of lost fish.

2. Self-reporting with no real deterrent

Failure to notify is technically an offence, punishable by fine. Yet there is no record of a single prosecution for failure to report an escape, and enforcement has relied instead on more informal compliance measures like improvement notices.

3. Systemic, invisible leakage of smolts

The industry does not count individual smolts into sea pens; it estimates stocking numbers from weight. Smaller fish can pass through minor net damage that would never register as a “catastrophic” or notifiable, or even noticeable incident. The logical conclusion is that routine, low-level leakage of post-smolts and small salmon is built into the system – and almost entirely unrecorded. No credible penalty regime can fix what is, in effect, a design feature of open-net cage farming.

Reckless regulation

Scotland has had no dedicated financial penalties for escapes, despite repeated recommendations from the Salmon Interactions Working Group that proportionate fines should apply and should help fund wild salmon conservation.

In response to this growing concern, Cabinet Secretary Mairi Gougeon indicated in September – just before the Loch Linnhe escape disaster – that Scottish Ministers “will prioritise progress on financial penalties for fish farm escapes in 2026/2027“. To set that timeline against reality:

- The Loch Linnhe escape has already happened.

- Anglers and district salmon boards are dealing with the consequences now.

- Wild salmon populations are on a crisis footing now.

Deferring an effective deterrent for another legislative cycle is not a precautionary response; it is reckless institutional procrastination.

A double standard, owned abroad

There is a further damning detail which makes clear that Scotland should not have to put up with this procrastination. The dominant salmon farming companies operating these sites are Norwegian-owned. In Norway, Mowi was fined NOK 3.7 million (roughly £300–350k) after an escape of 54,000 salmon in 2018. In Chile, a mass escape at a Mowi site attracted a multi-million pound penalty.

In Scotland, by contrast, the same corporate groups are allowed to operate with relative impunity. There are no escape-specific fines, despite high-profile incidents including Loch Linnhe. The message is difficult to escape: the environmental risk by these companies is being exported; the regulatory seriousness is not. For a country that trades heavily on its reputation for environmental leadership, that contrast is an embarrassing failure of governance.

These fish are intensively stocked, selectively-bred animals in pens. Wild Atlantic salmon are not naturally a dense shoaling species; forcing them into high-density open nets is an industrial compromise, not an approximation of their ecology. When those nets fail, large numbers of maladapted, farm-bred fish are suddenly introduced into systems already struggling to support their wild counterparts.

Each escape is therefore not just a technical breach of containment. It is a foreseeable outcome of an open-net model whose margins depend on stocking densities, exposed sites and equipment that can and does fail. Indeed the industry is proposing to target its expansion in increasingly exposed offshore sites, where doubtless community and regulatory oversight will be even harder.

If we are serious about safeguarding wild salmon, then our Scottish Government must take action now, not in “2026/2027”:

- Penalties for escapes must be immediate, substantial and in force before the next major incident, not after it.

- Reporting must be independently verified, including better oversight of transport losses and leakage of smolts from farms.

- Policymakers and politicians must urgently confront the structural reality that open-net salmon farming, as currently practised, makes such “escapes” inevitable – and that asking volunteers in our rivers to clear up after multinational companies is not a credible regulatory strategy.

We have the power to break this cycle. Every time we choose NOT to buy farmed salmon, we’re protecting wild fish populations and Scottish waters while standing up against a multinational industry that prioritises profits over the health of our seas and rivers. Visit Off The Table to join us today and take farmed salmon off your menu.

VISIT OFF THE TABLE

I really wanted to thank you for everything that you do…i fully support your farmed salmon campaign…disgusting way to treat sentient beings and the environment..i also had no idea that the amazon deforestation was so closely linked to this ghastly industry..mind boggling

Thank you for your continued support of our work.