We need to be cautious with family-level assessments of freshwater invertebrate biodiversity

A response to the recent Centre for Ecology and Hydrology research article – Qu et al, 2023.

On the face of it a research article stating “Significant improvement in freshwater invertebrate biodiversity in all types of English rivers over the past 30 years” must be a good thing… right? We are living in an age of ecological adversity and frankly it can be quite a depressing time to be working in the environmental sector, or even be a lover of nature. But this doesn’t mean that we should seek ‘good news headlines’ at the cost of suitable scientific scrupulousness.

A key issue with this research [1] is the methodology and although the authors do acknowledge the weaknesses, the majority of people aren’t necessarily going to read the full text and see these concessions. So, publishing the study under such a bold headline intended to make a splash in the field is at best misleading or at worst masking the problems facing freshwater invertebrates, and more broadly the state of our rivers.

Once effective infrastructure improvements to our waterways appear to be struggling to cope with modern day pressures

The headline and article message also contradicts other recently published scientific work, including a recent study [2] published in Nature, which reported that the recovery of European (including the UK) freshwater biodiversity has ground to a halt. Their mixed-level analysis of invertebrate abundance clearly demonstrates that there have been strong gains since 1968, but in recent decades these successes have plateaued (more information here). The gains seem to reflect the success of legislation and water quality improvements in the late 20th century while highlighting how these strategies appear to no longer be fit for purpose in the present day.

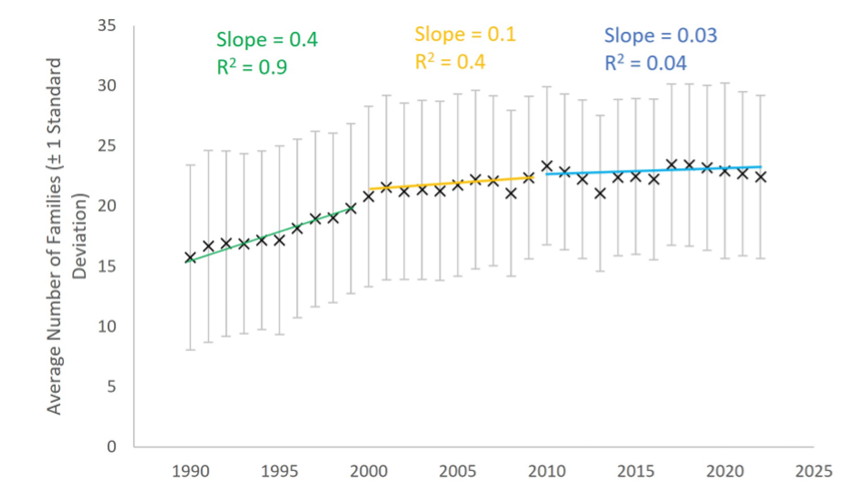

Our own analysis of openly available Environment Agency macroinvertebrate ecological datasets shows a similar story (Fig. 1). Undoubtably there has been an overall improvement during the study period. However, if we break this down by decade, we see strong gains in the 1990’s, smaller improvements in the 2000’s, and no significant improvement past 2010 – with potentially a year-to-year decline since 2017.b

It is positive that there has been an improvement to the state of our rivers since the 1980’s, which has been widely reported in the literature (e.g., 3, 4), but it we need to recognise that these improvements are relative to the very poor condition of rivers in the 1960s – 1980s and have stalled in recent years. We need to be putting out a call to arms to remedy the current situation, not patting ourselves on the back for work that was mostly completed 20 years ago.

Figure 1: Showing the annual average (±SD) freshwater invertebrate Family richness across English sites with trends colour coded by decade. Our interpretation of this is that the improvements primarily happened in the 1990’s and to imply that ‘biodiversity’ recovery is ongoing is somewhat misleading.

Currently, the agencies responsible for protecting our natural resources are chronically underfunded and the government appears to be actively backtracking on a variety of green policies. Research painting a glossier picture than the ‘reality on the riverbank’ risks detracting from the essential work conducted by various organisations who are actively trying to monitor, conserve, and restore the ecological health of our rivers.

We need species-level analysis to get a true assessment of the state of freshwater invertebrates

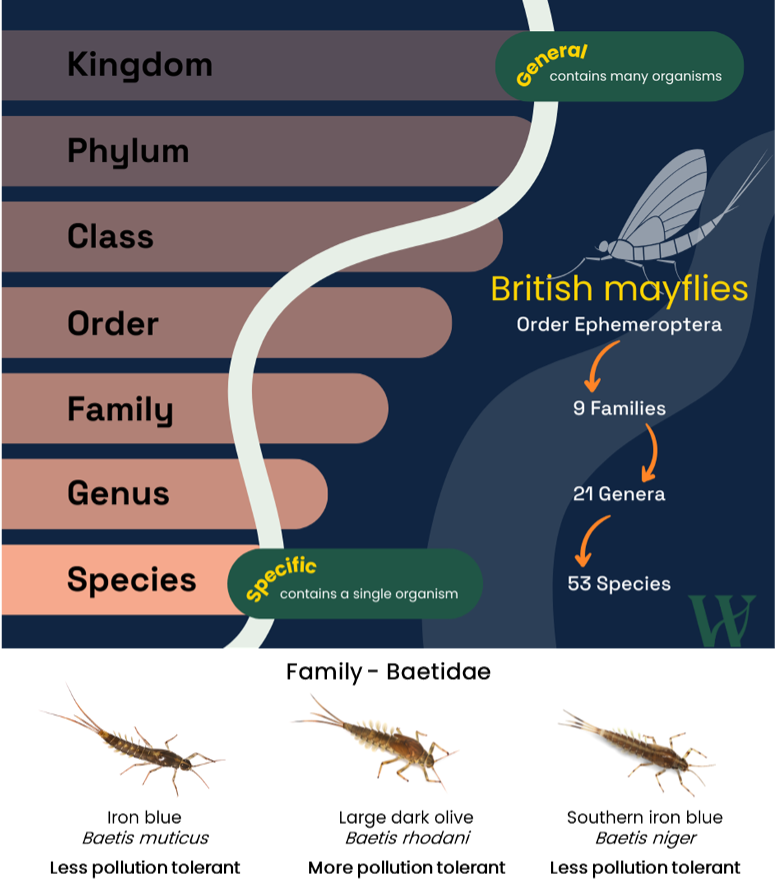

We also have concerns with the metrics used to assess freshwater invertebrate communities. The first issue is the taxonomic resolution used in this assessment. Biodiversity, i.e., the variety of life in a given area, is most commonly assessed at the species-level. While not necessarily a failsafe method for capturing the complexity of natural communities (e.g., it is also important to consider the numbers of individuals and where they are congregated) it does give us a greater level of detail when assessing ecological challenges. This is because an individual species can be tolerant or sensitive to a particular threat (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Demonstrating why analysing invertebrate samples at the species level will give higher resolution data. The top of the figure shows the taxonomic hierarchy and how many species sit within a single family, with British mayflies as an example [5] . The bottom of the figure shows how even within a group of insects traditionally thought of as pollution sensitive, there is variation that is lost with family-level analysis. Credits: Infographic – Lauren Harley. Images – Dr Cyril Bennett.

For example, within the mayfly family Baetidae the large dark olive is considered to be more pollution tolerant than closely related species like the iron blue or southern iron blue. You would only need one of these species to be present to tick the box for Baetidae, but the presence of southern iron blue at a site would be indicative of better water quality than a site with only large dark olives. The Qu et al study assesses richness at the family level and therefore key information is being lost. Such as, while family richness may have increased, the number of species within a family could have declined. Moreover, we do not know whether we have gained families with low numbers of species, while losing more species rich families.

The authors state that species-level and abundance data are patchy over the 30-year study period. This may be true… but we should therefore be very cautious about bold statements regarding an overall improvement to ‘biodiversity’.

Using outdated metrics risks obscuring important information regarding invertebrate communities

We also have concerns with the use of the Biological Monitoring Working Party (BMWP) score and its associated metrics as a way of assessing trends in the condition of invertebrate communities. The BMWP scoring system was introduced in the 1980’s [6] and has significant limitations that resulted in it being superseded by the WHPT index in 2015 [7, 8] . Put simply, BMWP results in invertebrate families being given a score of 1-10 with more pollution sensitive families scoring more highly. These scores are added to get the BMWP score or averaged to get the average score per taxon (ASPT), in relation to the number of families found (NTAXA).

Other than the lack of detail in a family-level metric, a key issue is that the BMWP system does not account for abundance. So, if one polluted site contained a single mayfly of a certain family and another less impacted site contained 1000 mayflies of the same family, both observations would score ‘10’ (as mayflies as a whole are considered pollution sensitive). Clearly the difference between a healthy population of pollution sensitive taxa and a population barely hanging on due to habitat/water quality is important and needs to be taken into consideration when assessing ecosystem health. Conversely, if we look at a more pollution tolerant taxonomic group like the Chironomidae (non-biting midges) if the numbers were in the 10’s or the 100’s both observations would score ‘2’, even though the latter example could be indicating an acute pollution problem at that site.

Clearly this is a flawed method to judge our rivers by and WHPT, although still family-level, reduces this effect by accounting for the abundance of the total community and within each family. The authors chose to use BMWP so they could include earlier samples due to the paucity of abundance data pre-2000. Regardless, the major limitations of using out-dated biomonitoring scores to make grand statements about ecological community health is problematic and, in this case, we argue it is highly misleading.

Abundance data can give key insights to current conservation issues

Additionally, not accounting for the abundances of the invertebrates in monitoring samples simply misses out on vital information. In this current study the authors state that invasive families (non-native invertebrates) on average ‘only’ increase from 1.0 to 1.3 families per site over the study period. But what does this mean in real money? Knowing family-level presence we argue gives no information as to the scale of potential problems. For example, invasive molluscs (primarily Asiatic clams) in the lower reaches of the river Thames are found in incredibly high numbers and appear to have almost completely replaced our native mollusc species in areas, comprising up to 96% of individuals [9]. That’s a terrifying figure and the ramifications of these numbers to key ecological processes and the food chain dynamics in our rivers are not fully understood.

While these ridiculous proportions of invasive species will not be present in waterways across the country (although anecdotally we’re aware of comparable issues on the Severn and Trent), it highlights why we need biodiversity measured at fine scale. Even in lower densities evidence suggests that invasive species have long-term effects on our native invertebrate communities. For example, following the invasion of signal crayfish there appear to be permanent reductions to the numbers of bottom-dwelling invertebrates, such as caddisfly larvae [10] . We need to know what species are present in our rivers and in what numbers in order to effectively identify and address conservation challenges on the ground.

What is a pristine river in the Anthropocene?

Then we can look at how invertebrates may be lauded as a ‘return to normal’ compared to the ‘pristine or natural state’ of rivers. The authors calculate an ecological quality index (EQI) which is a ratio of the observed data to a reference value predicted by the River Invertebrate Prediction and Classification System (RIVPACS) and BMWP indices. This is a standard statistical approach to assess rivers nationally; however, the limitations of such an approach are widely known, particularly for predicting species community structure [11]. In particular, the ‘ideal’ reference conditions are datasets from pre-1980s in rivers far from pristine. We have no unimpacted freshwater habitats in the UK and haven’t for a very long time. As such, reference conditions are better described as the best of a bad bunch, and we shouldn’t be limiting our objectives to hit these (realistically) subpar standards. In addition, climate and hydrological changes mean we cannot go back in time, we need to look forward and do the best we can do with the rivers we inherit today.

An improvement to biodiversity will be highly dependent on a rivers’ starting condition

It is undoubtable that improvements to freshwater invertebrate biodiversity have happened since the beginning of the study period. One of the reasons for this is likely to be the work that has occurred on our, historically, heavily industrialised rivers such as the Mersey, Thames, and Trent[12, 13] . During the 1990’s large investment was made through water company asset management programmes in these heavily polluted rivers. For example, £45 million was spent on the river Erewash improving its River Ecosystem class (RE: a historical classification scheme associated with the Nation Rivers Authority) from RE3/4 (fair quality) to RE2 (good quality)[14]. It is efforts such as this which are most likely responsible for the undoubtable improvements to the state of freshwater ecosystems that we see in the late 20th century. While this was essential work that has paid dividends (and ironically highlights what can happen with proper investment into infrastructure) it was a low hanging fruit with regards to the recovery of nature, i.e., when what was essentially effluent becomes a river again it’s hardly surprising that we see a marked increase in what is able to live in it!

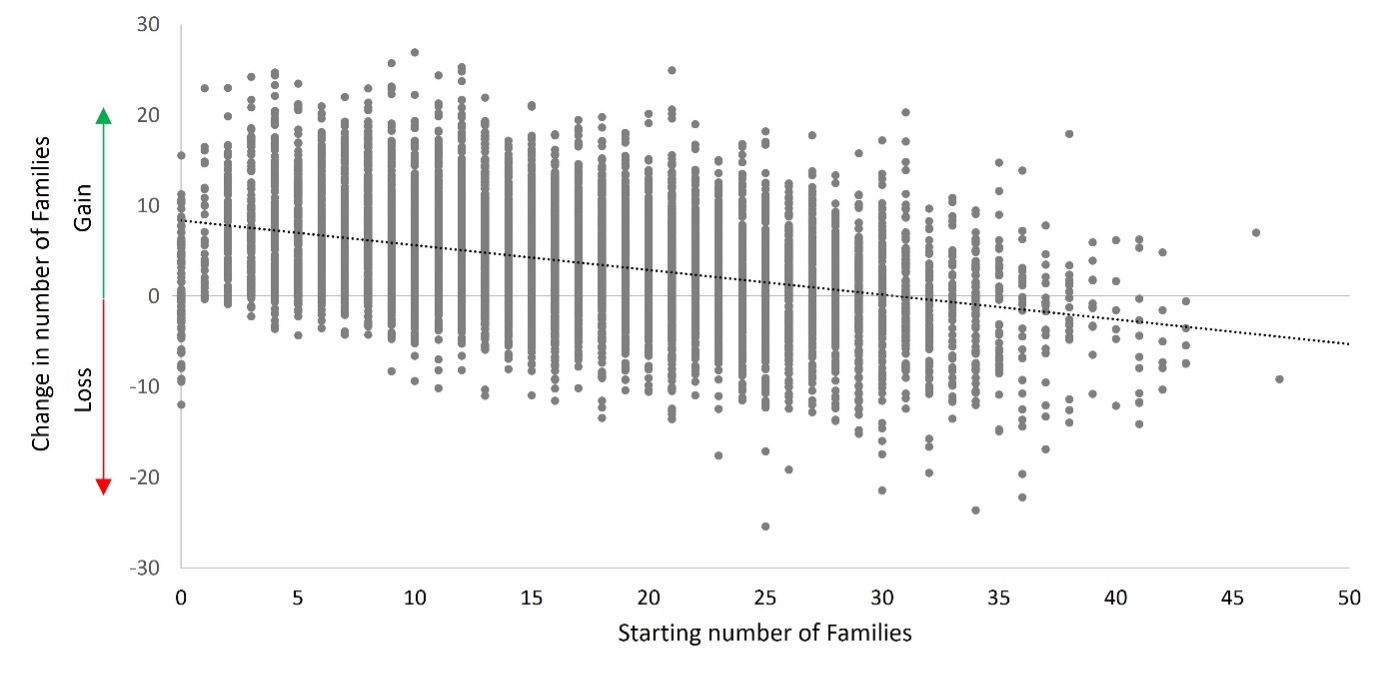

The presentation of these marked improvements over the 1990s and early 2000’s could also mask the finer detail, and such improvements may not be universal. For example, Fig. 3 shows that sites that initially had low family diversity (more degraded habitat) had the biggest improvements between 1990 and 2020, while sites that started with relatively high diversity (healthier habitats) have seen negligible improvement and in some cases, notable declines over the study period. Whilst this family-level analysis suffers the same issues mentioned above and should be read with caution, it does make the concerning point that historically focusing on cleaning up the bottom of the pile rather than making more broad changes to how we manage our rivers, could have lead declines in our healthier sites, with implications for some of our most vulnerable invertebrate species.

Figure 3: Demonstrating how increased freshwater invertebrate family richness may be driven by improvements in rivers that started off in worse condition (fewer Families), while rivers that started off in better condition (more Families) are not necessarily showing the same improvements.

We should celebrate the wins, but we need to acknowledge the current struggles our rivers are experiencing

It is absolutely right that we should be celebrating the recovery of freshwater invertebrates from the 1980s to the early 2000s, and much academic work already exists on exactly this topic[2-4]. It demonstrates that with proper investment in our infrastructure, and better legislation protecting these invaluable ecosystems, rivers are able to bounce back. However, it is disingenuous to imply that these successes are continuing to the present day or that river management over the past decade has improved ecological communities. This is simply not the case. You only have to look at the fact that only 14% of rivers in England currently have good ecological status or read about the current woes of the water companies with outdated water treatment facilities struggling to contend with a growing populations and more complex chemical inputs, to be aware that the current situation isn’t great. Such views are not just those of freshwater charitable organisations, but also the current academic consensus, as evidenced by the recent Nature paper making the same assertions

Investigations focused on the presence/absence of taxonomic families are simply not good enough to gain a strong understanding of how our invertebrate populations are coping, nor a basis to make gross assertions about river health. We argue that to assess and monitor ecosystem health, we need to be looking at true biodiversity; that is species richness and abundance. We’re not collecting Pokémon where a single individual is enough to tick a box. To truly recover, freshwater ecosystems must be robust and resilient, containing large abundances of individuals within diverse species, offering an interlinked network of ecological functions. If there simply isn’t enough data available to investigate population trends at this level, we should be extremely cautious about making sweeping statements about conservation successes.

Dr Sam Green is a freshwater ecologist working at WildFish, primarily supporting the SmartRivers invertebrate monitoring programme.

Dr Nick Everall (FIFM, C Env) is the Director of Aquascience Consultancy Limited. He has nearly 40 years of experience in a diverse range of water industry roles and a pioneer of the analytical metrics used to monitor river health.

List of references

- Qu, Y. et al. Significant improvement in freshwater invertebrate biodiversity in all types of English rivers over the past 30 years. Science of The Total Environment 167144 (2023).

- Haase, P. et al. The recovery of European freshwater biodiversity has come to a halt. Nature (2023).

- Outhwaite, C. L., Gregory, R. D., Chandler, R. E., Collen, B. & Isaac, N. J. B. Complex long-term biodiversity change among invertebrates, bryophytes and lichens. Nat Ecol Evol 4, 384–392 (2020).

- Vaughan, I. P. & Ormerod, S. J. Large-scale, long-term trends in British river macroinvertebrates. Glob Chang Biol 18, 2184–2194 (2012).

- Macadam, C. & Bennet, C. A Pictorial Guide to the British Ephemeroptera. Field Studies Council AIDGAP Guides OP139 (2010).

- Hawkes, H. A. Origin and development of the biological monitoring working party score system. Wat. Res vol. 32 (1997).

- Environment Agency. Walley Hawkes Paisley Trigg (WHPT) index of river invertebrate quality and its use in assessing ecological status. Brief Guide v. 10 (2019).

- Paisley, M. F., Trigg, D. J. & Walley, W. J. Revision of the biological monitoring working party (BMWP) score system: Derivation of present-only and abundance-related scores from field data. River Res Appl 30, 887–904 (2014).

- Himson, S. J., Kinsey, N. P., Aldridge, D. C., Williams, M. & Zalasiewicz, J. Invasive mollusc faunas of the River Thames exemplify biostratigraphical characterization of the Anthropocene. Lethaia 53, 267–279 (2020).

- Mathers, K. L. et al. The long-term effects of invasive signal crayfish (Pacifastacus leniusculus) on instream macroinvertebrate communities. Science of the Total Environment 556, 207–218 (2016).

- Everall, N. & Farmer, A. Evaluation of macroinvertebrate indicators and associated thresholds for favourable conditions. Aquascience Consultancy – AQ065/Natural England (2012).

- Langford, T. et al. The Unnatural History of the River Trent: 50 Years of Ecological Recovery. in River Conservation and Management vol. Chapter 21 (2012).

- Hawkins, S. J. et al. Recovery of an urbanised estuary: Clean-up, de-industrialisation and restoration of redundant dock-basins in the Mersey. Mar Pollut Bull 156, (2020).

- Everall, N. Personal Communication (2023).