What do we make of the Corry Review?

It has been no secret that successive Westminster governments have been slowly but surely trying to dilute environmental protections, prioritising economic growth over the environment.

Review after review has claimed, without real evidence, that environmental regulation harms business, or that it needs to be more “risk-based” and “light-touch” to avoid impacting economic growth (see, for instance, the work of the Better Regulation Task Force from 1997, the 2005 Hampton Review, the lead-up to the Legislative and Regulatory Reform Act 2006, David Cameron’s 2011 Red Tape Challenge, Lord Heseltine’s 2012 Report “No Stone Unturned”, the Regulators’ Code, and so on).

Each review has signalled yet more changes to weaken environmental protections.

Despite successive rounds, we are told that there is still too much red tape and it is restraining economic growth. [1]

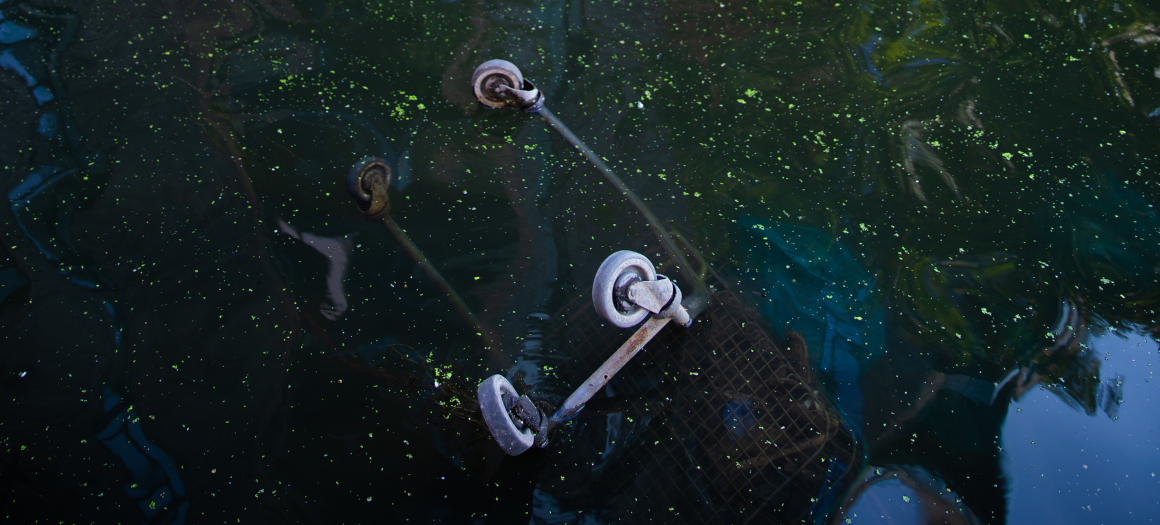

At a time when many are calling for regulators to start properly enforcing environmental law, for example against water companies after years of pollution to which OFWAT and the Environment Agency willingly turned a blind eye, the Government has made it clear that the aim is for yet further de-regulation.

The latest drive is to be found in the review of DEFRA’s ‘regulatory landscape’ conducted by economist, Dan Corry.

Corry’s report, “Delivering economic growth and nature recovery”, was published last week. [2] By his own admission, the author is “relatively new” to the subject (which perhaps sets alarm bells ringing). He provides an economist’s view on a plethora of regulatory law, set out under slightly random headings. Unlike his forerunners, Corry’s report begins with a two-fold assumption: that regulations don’t work and that businesses have suffered.

Corry paints a picture of economic stresses on those who are regulated. He portrays regulatory provisions and policies as too absolutist.

The key regulatory checks and balances (which habitually go unenforced, reference the OEP’s recent Decision Notices served on the Agency, OFWAT and DEFRA for failing to enforce regulations on sewage treatment over decades) are, according to Corry “stifling red tape”. He even coins a new phrase “green tape”.

Corry’s vocabulary of regulation is business orientated. The priority is to make the whole system more “navigable” for “customers” (in effect, those who may cause environmental damage if not subject to rules and regulations).

In a world where standards no longer apply as they used to (particularly across the Atlantic) the impression given is that a group of business interests and Treasury officials have arrived at DEFRA, espousing a utilitarian view of the world, and have announced that nothing is now off-limits in pursuit of economic growth.

But they do this without any real understanding of the purpose of the regulations that are now in their crosshairs.

Regulations for the chop?

Corry begins rhetorically with some numbers. There are 34 public bodies and agencies within DEFRA and over 3,500 pieces of legislation to have a pop at. [3] But centre stage is given to the small handful of key regulations that are arguably the mainstays of aquatic environmental protection in England.

Corry suggests a “rolling programme of reform” with the focus on the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017, The Conservation of Habitats and Species Regulations 2017, The Reduction and Prevention of Agricultural Diffuse Pollution Regulations 2018 (aka The Farming Rules for Water) and the Environmental Permitting Regulations 2016.

It is difficult to think of any environmental issues that don’t include something related to these key sets of regulations, especially in WildFish’s area of interest.

In other words, Corry is taking aim at the keystones of protection of the aquatic environment in England.

How, or who, identified these key sets of regulations as priorities for ‘reform’ is not made clear, but there is only a brief discussion of each, and Corry delivers little more than caricatures.

For example, with regard to agricultural pollution, Corry opines that there is “confusion around the relationship between the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017 targets (to achieve and maintain good ecological status in 75% of our water bodies by 2027), the Farming Rules for Water and a response to the Rapid Review of the Farming Rules for Water Statutory Guidance”.

A footnote refers us to a Wildlife and Countryside Link document which explains that the Statutory Guidance – but not the Farming Rules for Water themselves – is probably unlawful. It certainly does not suggest that the Farming Rules are inconsistent with the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017. Indeed, the Farming Rules (to give them their full title, the Reduction and Prevention of Agricultural Diffuse Pollution Regulations 2018) were made precisely to provide a legal measure that could be applied to help reach the ecological status targets set down in the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017.

And, in effect, all the Farming Rules did was to codify into law what had been in successive Codes of Good Agricultural Practice going back to the mid-1980s.

If there is confusion, it is perhaps because for decades agriculture has not been required by regulators to pay as much attention to the Codes of Good Practice, and now the Farming Rules, as the industry should have been?

Nevertheless, Corry asks the question as to “whether the feasibility of compliance was sufficiently tested before the regulations [the Farming Rules] were implemented”.

Had he understood the history of the Farming Rules, Corry would have known the answer. But perhaps, for Corry, just being able to question whether the Farming Rules can be complied with played better to his overall brief?

The “burden” of examples

As another example of the regulatory burden, Corry refers to Brent Reservoir in London, which had to be drawn down for engineering work requiring, among other things, an assessment under the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) (England and Wales) Regulations 2017.

One would have thought that such an assessment was just a common-sense step to protect the environment while doing necessary engineering to a waterbody that is valuable for wildlife, and to try to ensure, as far as possible, that ecological targets continued to be met.

Corry seems to be suggesting that we should just do away with such protections.

The Sheephouse Wood Bat Protection Structure is also held up as an example of conservation law gone too far. [4] HS2’s proposal to mitigate harms to rare species of bats includes a £1M ‘bat tunnel’. The case has indeed gained some notoriety, but this case is certainly not typical and is more due to the huge amounts of cash being wasted on consultants and their reports by HS2, than being an example of over-protection of sensitive and rare species that do need protecting.

Corry then points at delays to development caused by the knock-back for the Norwich Western Link dual carriageway, due to failures to mitigate the potential impact on the barbastelle bat. But what this example shows is that the system (sometimes) works. Presumably, most would read this as a positive outcome. If Corry’s implied view is that the conservation status of a rare species should usually be sacrificed in the name of economic growth, then that is a major blow for environmental protection in this country.

A similar example from the work being conducted by WildFish would be the real threat from large-scale housing development where there is insufficient capacity at sewage works. A proper regulator or a well-advised local planning authority would surely refuse to allow such development until it can be shown that local sewage works can cope with the extra flows that will need to be treated, and that there will be no extra pollution of rivers. That would not be an unnecessary burden, but a common-sense approach to follow to protect the rivers. Corry, it seems, would send in the diggers.

It is telling that Corry seizes on businesses as customers attempting fairly to operate in a difficult climate of regulation, and not in terms of operators needing to comply with permits, licences and permission all designed to prevent harm to the wider ‘public’ environment.

The case study of the Environment Agency’s prosecution of Suez Recycling and Recovery Limited for no fewer than 32 breaches of permits at its Connon Bridge landfill site is cited by Corry to demonstrate that the regulator should always engage with waste companies rather than prosecuting them, even where there are multiple offences being committed. Corry does not mention what effect the absence of a robust deterrent might have on the behaviour of all would-be polluters, including Suez itself.

Streamlining

Corry also suggests there should be “streamlining” for key regulations, so that decision-makers do not face judicial review for not following the “letter of the law”, presumably thereby causing delays and hampering economic growth.

But these regulations are there to protect and enhance the environment – not to serve business.

In any event, the law already provides for over-rides, when economic activity must be the priority. Take the Water Environment (Water Framework Directive) Regulations 2017 that Corry has in his sights. If there are circumstances where the public interest is best served by an activity or development which may damage a river and its chances of meeting the ecological targets, then there are exemptions in the law for that very purpose.

Taming the Office for Environmental Protection?

One of the most alarming recommendations relates to the Office for Environmental Protection (OEP).

Presenting no arguments as to why the OEP needs to change, given it has only been in existence for a very few years, Corry says that “the OEP must ensure its focus is on outcomes not just process… Consideration should be given as to how the OEP can increase focus on the outcomes that are desired and support regulators to take more risk to achieve those goals within the Government’s wider objectives”.

Back to “the Government’s wider objectives…”

Put another way, Corry is suggesting that the post-Brexit environmental watchdog must fall in line and compromise to help Government achieve, primarily, economic growth.

But that is not the role of the OEP. Nor should it be.

It is vital that there is a body independent enough to examine whether environmental law is being complied with, to point out when the emperor has no clothes.

Could Corry taking aim at the OEP perhaps be a reaction to the OEP’s early successes, including the finding that DEFRA, OFWAT and the Agency have all failed to comply with their statutory duties in relation to the regulation of the use of storm overflows by water and sewage companies. That failure has meant that water companies have been allowed to continue, for decades, polluting rivers without investing to update treatment works and provide sufficient capacity. Investment that – Corry, please note – would have led to increased economic activity. [5]

What is Corry really all about?

Let’s be very clear here. Corry is about circumventing environmental protections to allow economic growth at all costs.

This is underhand and dishonest.

If the Government wants to de-prioritise environmental protections, the approach it should take is to seek to change the law, after an open and honest debate in Parliament, so we can all take a view on what is being proposed here.

The message from Corry, much like that from the Cunliffe Review and any number of other Government consultations, is that reform is required with the sole purpose of driving economic growth. The customer, for Corry, is business.

Make no mistake, the protection of the environment is slipping down the agenda.

List of references

1. See “Doing its Job?” Environment Agency Report | Wildfish The report lists wave upon wave of deregulatory measures: Regulatory Reform Act 2006; The Legislative and Regulatory Reform (Regulatory Functions) Order; Regulatory Enforcement and Sanctions Act 2008; Environmental Civil Sanctions (England) Order 2010; Environmental Civil Sanctions (Miscellaneous Amendments) Regulations 2010; the Regulator’s Code (published 2014); the Deregulation Act 2015 and so on. We could also add to this list the changes brought in by the last government by the Levelling up and Regeneration Act 2023.

3. The reason for the high numbers of regulations and public bodies is perhaps obvious. These cover separate areas of environmental regulation for different industries and where not all regulations apply in every situation; and not all those regulated are regulated by all agencies. Most of the regulations will be highly specialist and only used in particular circumstances, such as in the nuclear industry or the waste sector.